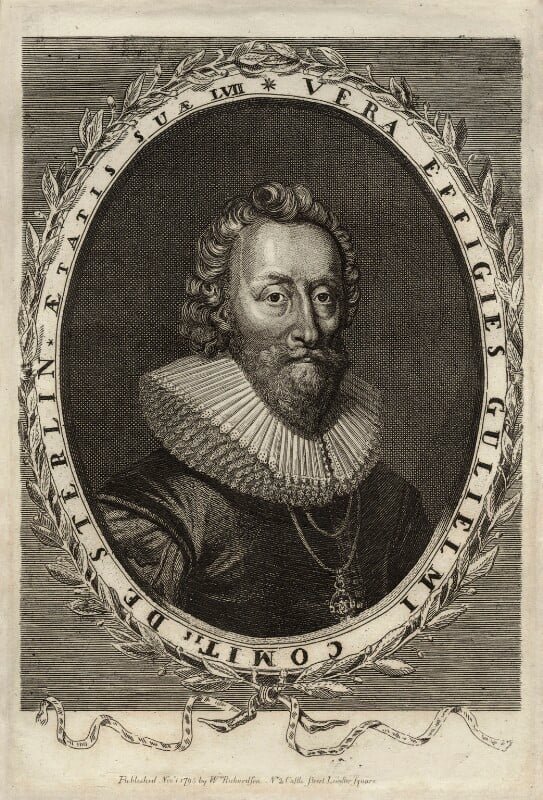

William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling (c. 1567–1640), was a Scottish courtier and poet. A prominent figure in the annals of Nova Scotia’s history, Sir William Alexander left an indelible mark as a knight, baronet and geopolitical visionary.

Born in Menstrie, Clackmannanshire, Scotland in 1567, Alexander’s life unfolded against the backdrop of a dynamic era marked by exploration, colonisation, and the forging of new territories. He served as the Secretary of State for Scotland from 1626 to 1640 under King Charles I. He was created Earl of Stirling on 14 June 1633. Later, as a result of his assistance with British colonisation efforts, he was also granted a Canadian title.

The son of Alexander of Menstrie and Marion, daughter of an Allan Couttie, he was educated at Stirling grammar school and there is a tradition that he studied at the University of Glasgow; and, according to his friend, the poet William Drummond of Hawthornden, was also a student at Leiden University, the oldest university in the Netherlands. His European travels also included trips to France, Spain and Italy as the tutor to the Earl of Argyll.

This relationship would prove fruitful. He was later introduced by Argyll to the court of King James VI in Edinburgh, taking on the role of a courtier-poet, and when James became the first Stuart king of England in 1603, William became one of the senior Scottish aristocrats who moved with him to London when James set up court there.

Utopian New World Visons

Sir William Alexander’s legacy is intimately tied to his role as a Scots with big colonial ambitions. His dream was to establish a Scottish presence in the Americas, and this vision materialised when King James VI of Scotland (later James I of England) granted him a charter in 1621 for lands in north-western Newfoundland that included parts of modern-day Canada and the north-eastern United States that would eventually became New Scotland (Nova Scotia), despite rival French claims. In this sense, he figures into our story from the perspective of utopian idealism and the connection many people at that time were making between the paradisal concept of Arcadia and the New World.

As the Baronet of Nova Scotia, Alexander was not merely a dreamer; he actively participated in the administration of the territory. He sought to attract settlers, offering land grants and incentives to those willing to make the journey across the Atlantic.

Alexander’s colonial vision faced significant challenges though, and the full realisation of his dream proved to be elusive during his lifetime. Despite facing numerous challenges, including conflicts with the French and the local indigenous peoples, Alexander’s efforts laid the groundwork for the later development of Nova Scotia when subsequent waves of Scottish migration led to the establishment of Nova Scotia as a distinct cultural and historical entity. Although he never actually visited North America, he is remembered for providing Nova Scotia with its name, flag, and coat of arms.

Books as Propaganda

Beyond his colonial ambitions, Alexander was also a prolific writer and poet. His literary contributions ranged from poetry to dramatic works. He specialised in ‘closet dramas,’ that is, plays not intended to be performed publicly. One of his notable publications is An Encouragement to Colonies, a work that encapsulated his zeal for promoting colonisation in the Americas. His other literary works include Aurora (1604), The Monarchick Tragedies (1604-07) and Doomes-Day (1614, 1637). Alexander also assisted the King in the preparation of the King James version of The Psalms of King David, and as reward for his services, he was awarded a licence to be their sole printer. As it happens, the biblical psalms are quite significant within Rosicrucian and Freemasonic lore (on which, see more below) – perhaps a hint that he (and the king) may have had Rosicrucian sympathies?

For example, a mysterious document entitled Recherches sur les Rose-Croix (Researches into the Rose Cross), deposited anonymously in the Bibliothèque Nationale circa 1623, claims that:

Their [i.e. the Rosicrucians’] religion is drawn exclusively from Genesis, from the book of Wisdom, and the Psalms of David, but they approach them with a formal conception to create a semblance that these great personalities wrote only to justify their own belief. In this endeavour they are greatly assisted by

Ms.Dupuy 550

their knowledge of the roots of languages.

Many scholars believe that Alexander actually used his literary works as rhetorical devices or persuasive tools to actively engage in early Jacobean debates and garner support for his vision of British colonisation and were partly devised as counsel for King James I on foreign policy and empire-building, both in Europe and abroad. In this sense, Alexander was no different to printers and publishers like William Caxton and Eustache Vignon as well as writers like Johannes Valentin Andreae, who all used this mew mass medium to spread their messages and influence public opinion.

Like Shakespeare‘s political tragedies, Alexander’s plays in particular, often use allegorical tales based on historical/mythical figures of conquerors like Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar to warn against excessive empire-building and to promote instead a philosophy of imperial moderation that would make James I both a peaceful and a successful empire builder and ruler.

His series of tragedies, especially the 1607 version of the Monarchicke Tragedies, also connect him to Block C on our Green Man trail – something we will discuss in greater detail in a separate video or post.

Links to Freemasonry

Sir William Alexander’s affiliations extended beyond the realm of literature and colonial administration; he was also connected to the Masonic fraternity. He became a member of Mary’s Chapel Lodge in Edinburgh in July 1634 .

Freemasonry, with its emphasis on brotherhood, esoteric symbolism and shared humanitarian values, found resonance with many intellectuals and visionaries of the time. As a Freemason, Alexander would have been part of a secretive and influential network – one that may well have included King James I. In some accounts, James was initiated into Freemasonry via the Scottish Lodge of Scoon and Perth in 1601, at the age of 35 – well before he was crowned King of England, which is why the 1611 edition of the King James Bible remains the Freemason Bible, according to the authors of The Hiram Key.

Freemasonry often facilitated connections among its members, transcending national boundaries via a common bond of shared ideals about knowledge, enlightenment, progress and exploration, many of which align closely with the spirit of colonisation and global expansion. These connections could have been valuable for someone like Alexander, who was involved in both the Scottish and English courts, aiding him in realising his political ambitions and colonial endeavours.

Freemasonry, together with his earlier European studies and travels, may also have introduced him to related esoteric organisations and/or religious or utopian concepts such as Rosicrucianism, which has a lot in common with Freemasonry.