Sir William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 1520 – 4 August 1598), was an English statesman and the chief adviser to Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign. He served twice as Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and was the Lord High Treasurer from 1572 onwards.

Protector of the Realm

Cecil was a master of Renaissance statecraft, whose talents as a diplomat, politician, and administrator won him high office and a peerage. His main goal of English policy was the creation of a united and Protestant British Isles.

William Cecil’s influence on Queen Elizabeth I’s reign extended beyond mere administrative duties. His role was pivotal in shaping the ideological foundations of Elizabethan England. Cecil shared a deep Protestant faith with the queen and was committed to securing the Protestant succession. Together, they navigated the complex religious landscape of the time, countering Catholic threats while avoiding extreme Protestant elements that could destabilise the realm. To this end, Cecil persuaded the Queen to order the execution of the Roman Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1587 after she was implicated in a plot to assassinate Elizabeth.

Cecil was instrumental in establishing a sophisticated intelligence network, utilizing individuals like John Dee, a renowned mathematician, astronomer, and occultist. Dee’s skills were harnessed for matters of espionage, cartography, and secret communications. This collaboration contributed to the security of England, especially during times of external threats, such as the tensions with Catholic Spain.

Patron of the Arts

Cecil, a patron of the arts, played a role in fostering intellectual and artistic endeavours – an important element of the Crown’s propaganda machine. He supported the likes of Philip Sidney, a prominent courtier, poet, and soldier. Sidney’s works, such as the pastoral romance Arcadia, reflected the courtly culture of the Elizabethan era. The Cecilian circle also included Sidney and Edmund Spenser, whose tribute poem to Elizabeth I, The Faerie Queene, contributed to the flourishing literary scene, embodying the Renaissance spirit of the time.

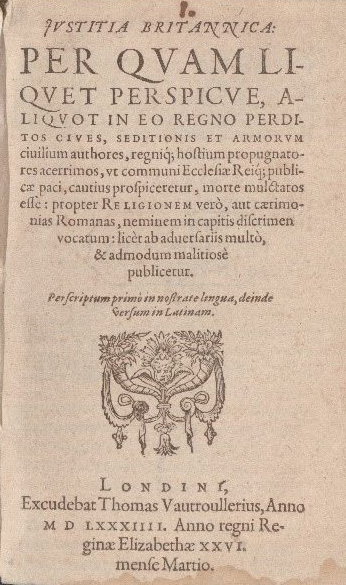

In 1584, William Cecil published Justitia Britannica, a seminal work on law and justice in Britain, reflecting his profound insights on the subject. The significance of this publication goes beyond its legal discourse, as it introduces the presence of the Greenman, specifically Block G, a symbol featured within the Fama of the Rosie Cross. Strikingly, this marks the inaugural appearance of Block G in London, and notably, it occurs within the publication of one of the most influential figures in England—William Cecil.

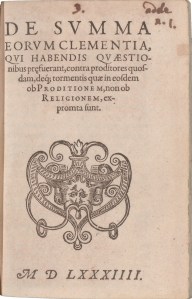

Yet, delving into the symbolic connections between Justitia Britannica and the Rosie Cross prompts a reconsideration of assumptions. This revelation challenges conventional perceptions and raises the intriguing possibility that William Cecil – or perhaps his printer and bookseller, Thomas Vautrollier, a Huguenot refugee from Troyes in Champagne, France – might indeed have been a Rosie Cross sympathiser. It is Vautrollier’s printer’s ornament that graces the frontispiece for the 1594 edition of the Justitia Britannica below is a version bearing his initials. As we’ve already seen elsewhere with printers like Eustace Vignon, Huguenots felt a strong sense of obligation to evangelise about the Reformation cause in whatever way they could, believing it would free people from the authoritarian grip of Papal Rome and its agents, including the French state and the Spanish Inquisition.

Protestant Utopianism

Considering Cecil’s background and well-documented history, the notion that he could be affiliated with the secretive brotherhood of the Rosie Cross seems implausible. However, he was a stanch Protestant deeply committed to the Reformation, both at home and abroad. As a statesman, he was interested in creating an ideal Protestant Polity and Christian Commonwealth based on what he termed a ‘confessional state,’ governed by a network of officials loyal to Crown and Church who were committed protestants. In private memoranda, Cecil insisted that the security of the realm was dependent on lawmakers and magistrates who possessed an ‘inward’ Protestantism ‘of the heart.’ One could argue that he shared a form of Protestant Utopianism of the kind we see in people like Johann Valentin Andreae, the alleged author of the Rosicrucian trilogy, combined with the political idealism of Sir Francis Bacon, who also wrote about a utopian-like state he called the New Atlantis, in a similar vein to Plato’s Republic.

So, what is it about the book that suggests Cecil may have been a Rosicrucian sympathiser? Before us lies a significant page within the publication, sharing its space with the identical Greenman block seen in the Fame and Confession of the Rosie Cross in 1615. Notably, though, this connection predates the printing of the manifestos by a full 30 years. Such evidence underscores the idea that the manifestos represent merely a fraction of an extensive and longstanding movement that has wider and deeper roots than simply that of a mystery religion. It suggests that the groundwork for this enigma was laid long before the manifestos even entered the realm of print. This revelation prompts a broader exploration of the multifaceted layers that contribute to the overarching narrative of the Rosie Cross, inviting us to delve deeper into the historical and socio-economic background that led to the inception of this mysterious tradition.

Legacy

William Cecil’s contributions laid the groundwork for the flourishing Elizabethan Age, characterized by a synthesis of political stability, cultural achievements, and a sense of national identity. His collaboration with figures like John Dee and support for intellectuals like Philip Sidney contributed to the intellectual and artistic vibrancy of the period.

Upon his death in 1598, Cecil left a legacy. His son, Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, succeeded him as the principal secretary and continued his father’s work. Robert, like his father, played a crucial role in the court of James I. Since then, the Cecil dynasty has gone off to produce many politicians including two English prime ministers.