MATHEMATICIAN, LAWMAKER & SCIENTIST

Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626), also known as Lord Verulam between 1618 and 1621, was an English philosopher, lawyer and statesman who served as Queen’s counsel to Elizabeth I, and Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I.

A bright and precious child, Bacon was initially home schooled due to ill health with the help of John Walsall, an Oxford graduate with a strong leaning toward Puritanism. At the age of 12, Bacon was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was tutored for three years by the future Archbishop of Canterbury. Bacon’s education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. It was also here that he met Queen Elizabeth for the first time. Bacon later stated that he had three goals in life: to uncover truth, serve his country, and his church. In this, he sounds remarkably similar to his uncle by marriage, Sir William Cecil. Like Cecil, Bacon would go on to be an MP, sitting in 1588 for Liverpool; 1593 for Middlesex and three times for Ipswich in 1597, 1601, 1604, and once for his alma mater, Cambridge University in 1614.

Like John Dee, he was also a bibliophile and a patron of libraries. In typical Baconian fashion, he developed his own system for cataloguing books under three broad categories – history, poetry, and philosophy. He is alleged to have said about books: “Some books are to be tasted; others swallowed; and some few to be chewed and digested.”

In addition to being a brilliant mathematician, he also led the advancement of both natural philosophy and the scientific method, and his works remained influential even in the late stages of the Scientific Revolution. Bacon has also been called the father of empiricism.

Bacon & the Royal Society

An admirer of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (though he later refuted some of Aristotle’s theories, creating an ‘improved’ version of them himself), he argued for the possibility of scientific knowledge based only upon inductive reasoning and careful observation of events in nature, rather than just theorising hypothetically. For this reason, him is often credited as the inspiration for the creation of the Royal Society.

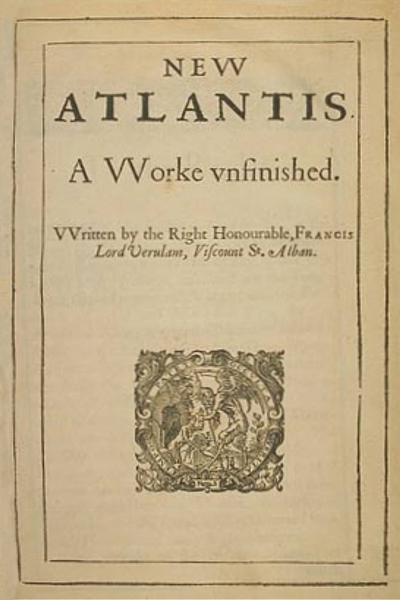

This is largely due to Bacon ‘s New Atlantis (published incomplete in 1626), in which he presented the idea of a utopian scientific institution that promotes research and called it Salomon’s House in homage to the wisdom of the Biblical King Solomon. Some, such as the historian Peter Dawkins, see this as a Masonic reference and suggests that Bacon, like men erudite and illustrious men of the period, may have been a member of this secretive fraternity.

The Royal Society itself was founded by a group of eminent British scientists, philosophers and philanthropists in 1660, several decades after Bacon’s death. Nonetheless, the society sought to realise Bacon’s vision of experimental science as a collective activity undertaken for the good of the state. So, while Francis Bacon was not a founding member, his philosophical ideas greatly influenced its formation and principles. His emphasis on observation, experimentation, and the sharing of knowledge laid the groundwork for the scientific method, which is central to the work of the Royal Society

In almost every field he gravitated towards, from law to maths and science, there is a common thread, which we could interpret as being to create and follow rule-based systems and laws.

Codes & Ciphers

Bacon was also fascinated with ciphers and codes, read/spoke several languages, including Latin and Greek.

In fact, he devised his own cipher, known as Bacon’s cipher or the Baconian cipher, in 1605 (see right). This method of steganographic message encoding concealed a message in the presentation of text, rather than its content. To encode a message, each letter of the plaintext is replaced by a group of five of the letters ‘A’ or ‘B’. This replacement is a 5-bit binary encoding and is done according to the alphabet of the Baconian cipher. His work in this area is believed to have later inspired the creation of Morse Code and the binary code of modern computer technology.

Bacon considered ciphers central to the so-called Art of Transmission, the general study of discourse and writing. His interest went beyond common letters and languages, however; he was interested in Chinese characters, as well as in the sign language of the deaf. In this sense, he understand that all language, especially written language, is a form of symbolism.

Bacon also made use of several different kinds and types of cipher, some of them to sign various published works issued outwardly under different names or pseudonyms, some of them to give signposts, messages or teachings, some of them to provide geometric constructions, and some of them being a method by means of which to analyse and raise consciousness, and ultimately to know the metaphysical laws and intelligences of the universe.

Bacon’s interest in ciphers was not just for sending letters in code. He also saw the potential of ciphers in the decryption of nature. By invoking the example of codebreaking, he prepared for the later union of mathematics with experimental science. His work in this area laid the groundwork for the development of symbolic mathematics2.

Bacon’s interest in hidden meaning within texts also extended to a form of medieval textual exegesis, which he no doubt learned as part of his medieval education. In 1609, he wrote a book called The Wisdom of the Ancients, in which he playfully claims to unveil the hidden meanings and teachings behind ancient Greek myths and fables.

Baconians often point to cryptic codes or ciphers they believe Bacon left within the plays of Shakespeare as evidence of his authorship. They also argue that certain themes, styles, and vocabulary in the plays align more closely with Bacon’s known works and interests than with Shakespeare’s biography. We will examine this idea more closely further down.

The Real Shakespeare?

Central to the mystery surrounding Bacon is the enigma of Shakespeare’s authorship. The publication of the First Folio in 1623, a posthumous compilation of William Shakespeare’s plays, has fuelled speculation about the identity of the Bard. Some proponents of the Baconian theory posit that Bacon, with his intellectual prowess, linguistic mastery, and deep understanding of the courtly milieu, may have been the concealed hand behind the Shakespearean works

The Baconian theory of Shakespearean authorship, which was first proposed in the mid-19th century, suggests that Sir Francis Bacon wrote the plays traditionally attributed to William Shakespeare. The main premise of this theory is that the learned and high-ranking Bacon would have been unable to openly produce plays for the public stage without risking his social standing.

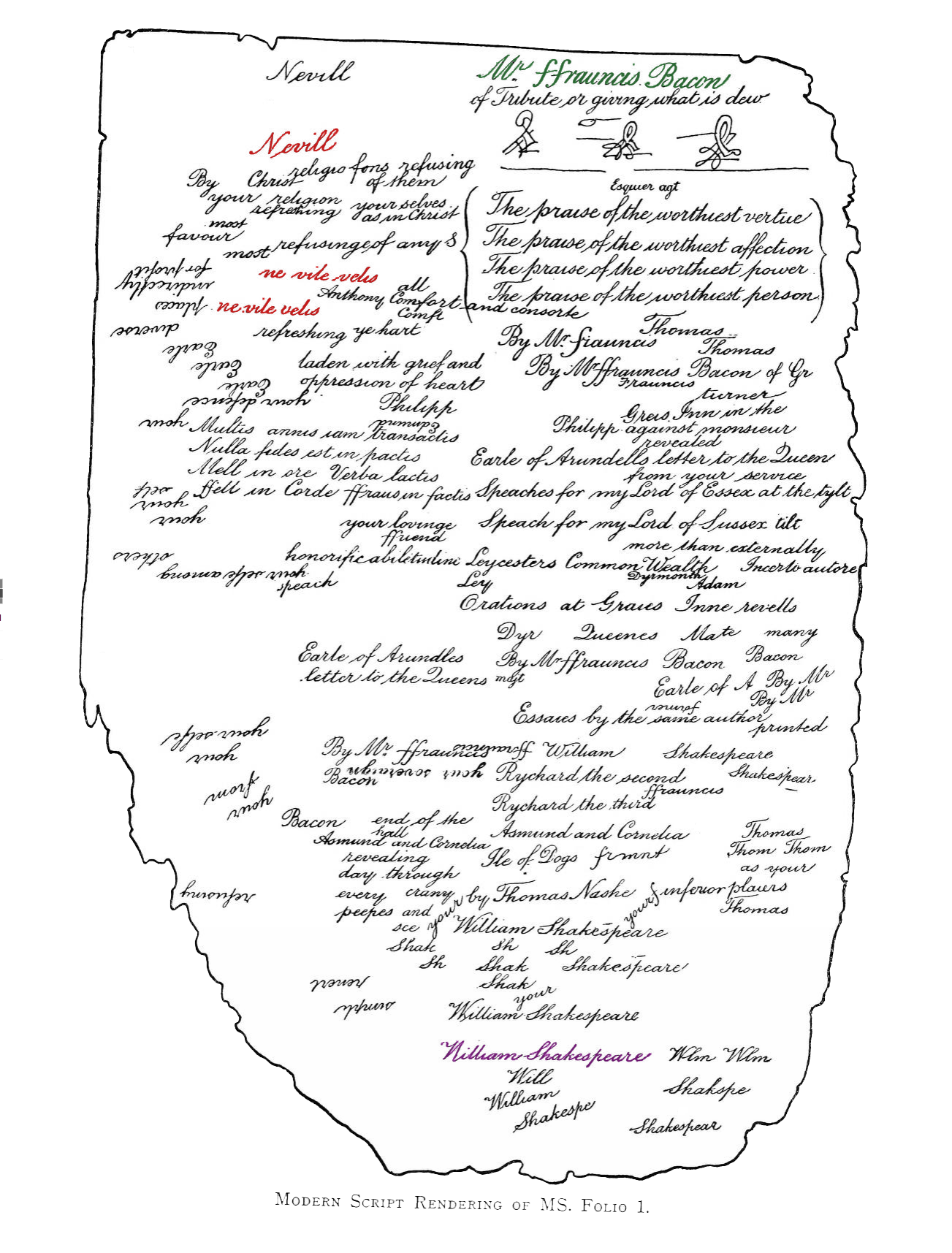

Much of the historical evidence for this rests upon a document known as the Northumberland Manuscript, Nestled within the pages of this manuscript, both their names share a space, forming a nexus that beckons scholars, historians, and enthusiasts into a realm of tantalising possibilities. According to the Shakespeare Authorship Trust, this document originates from Bacon’s scrivenery, and ‘lists works by Francis Bacon that include two Shakespeare plays, Richard II and Richard III, with the direct inference that Bacon was their author.’ The society also alleges that Bacon’s friend, Tobie Matthew, wrote in a letter that Bacon was known to the world under another name.

However, mainstream scholars reject the Baconian theory. They argue that the theory relies on conjecture and the distortion of historical facts, and that it ignores the wealth of evidence that points to Shakespeare of Stratford as the true author. For instance, there are numerous contemporary references to Shakespeare as a playwright, and his acting troupe performed many of the plays, both at the Globe Theatre and at Court.

In conclusion, while the Baconian theory has its followers, it is not widely accepted among mainstream scholars. The consensus is that William Shakespeare, the actor and businessman from Stratford-upon-Avon, is indeed the author of the plays and poems that bear his name.

Was Bacon a Rosicrucian?

Claims that Bacon directed the Rosicrucian Order and its activities both in England and on the continent have long existed. Bacon’s alleged connection to the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons has been widely discussed by authors and scholars in many books, including those of Frances Yates and Jocelyn Godwin.

However, others, including Daphne du Maurier in her biography of Bacon, have argued that there is no substantive evidence to support claims of involvement with the Rosicrucians.

Tobias Churton, who many consider to have written the definitive history of the Rosicrucians, and an initiate himself, feels that, although it might be tempting to view Bacon as a secret Rosicrucian Bacon’s ideas and activities have so much in common with those of the Rosicrucian movement, this might be premature. For one thing, there is very little evidence to suggest that the order itself even existed as a proper fraternity until a few generations after Bacon.

However, Churton goes on to admit that both Bacon and Johannes Valentin Andreae (who many believe wrote the Rosicrucian trilogy) had a lot in common. Both were brilliant mavericks and original thinkers who were ‘both keenly aware of the shortcomings of their times, and both proposed original ways of coping with the intellectual and spiritual shortfall of their era’.

Shared Utopian Vision

The link between Bacon’s work and the Rosicrucians’ ideals which Yates allegedly found involved a certain conformity of the purposes expressed, both in the Rosicrucian Manifestos and Bacon’s plan of a “Great Instauration.” Like many individuals and organisations at that time, both were calling for a reformation in society – not just in terms of a more enlightened worldview that encompassed both “divine and human understanding,” but also for a new age – one that involved mankind’s return to the “state before the Fall.”

Bacon’s connection to Protestant Utopianism is also evident in his work New Atlantis (published incomplete in 1626). His idea of a new society also converges with romanticism around the discovery of the New World, which many protestants and puritans saw as an opportunity to start again, away from religious persecution happening in Europe .

It is possible that this utopianism became focused on the New World. Certainly, there is evidence that this was the case in many of the books published by Huguenot publishers like Eustace Vignon. This idealism may well have rubbed off on certain groups who immigrated there, hoping for a better life, perhaps with a view to making Bacon’s New Atlantis (or indeed, the Protestant Utopian state) a reality.

An added bit of intrigue is that Bacon became Governor of Newfoundland in 1618. His tenure in this colonial post unfolded against the backdrop of burgeoning exploration and expansion. The remote shores of Newfoundland may well have become a canvas upon which Bacon could paint his utopian vision.

Some have also argued for his involvement in the publication of the first English translation of the Rosicrucian manifestos the Fama and Confessio (1652) and the publication of the unique version of his New Atlantis known as The Land of the Rosicrucians (1662).

The modern day Rosicrucian organization, AMORC claims that Bacon was the “Imperator” (leader) of the Rosicrucian Order in both England and the European continent, and would have directed it during his lifetime. However, there is very little evidence for this. It is either the case that the organisation was indeed so secretive that his links were hidden, or it may be the case that the order itself was more of an idea than an actual fraternity, at least in the beginning anyway, as Churton has robustly argued.

Frances Yates also does not claim that Bacon was a Rosicrucian, but instead, presents evidence that he was nevertheless involved in some of the more closed intellectual movements of his day (perhaps the so-called Invisible College) – fitting for a man of his stature and social position. We do know, for instance, that he often gathered with the men at Gray’s Inn to discuss politics and philosophy, and to try out various theatrical scenes that he admitted writing.

Nonetheless, Bacon’s influence can also be seen on a variety of religious and spiritual authors, and on groups that have utilized his writings in their own belief systems.

Was Bacon interested in the Occult?

Bacon’s intellectual pursuits extended beyond the conventional, delving into the esoteric and the mystical. As we navigate the labyrinth of Bacon’s life, the question arises: did his philosophical pursuits extend into the clandestine realm’ of the Rosicrucians? Or any secret fraternity or mystery school within the Western esoteric tradition?

Peter Dawkins argues that Bacon was a secret Christian Cabbalist, and was posthumously called Tertius a Platone, Philosophiæ Princeps (i.e. the third Plato), on the frontispiece to the 1640 edition of Bacon’s Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning. This Latin description of Bacon translates to ‘The third from Plato, the leader of philosophy,” implying that Bacon was perceived as the successor to the Italian Renaissance magus and scholar, Marsilio Ficino, a member of the Florentine Platonic academy who many called the Second Plato.

While rejecting occult conspiracy theories surrounding Bacon and the claim Bacon personally identified as a Rosicrucian, the intellectual historian Paolo Rossi has argued for an occult influence on Bacon’s scientific and religious writing. He argues that Bacon was familiar with early modern alchemical texts and that Bacon’s ideas about the application of science had roots in the Renaissance revival of hermetic ideas about science and magic facilitating humanity’s domination of nature.

Rossi further interprets Bacon’s search for hidden meanings in myth and fables in such texts as The Wisdom of the Ancients and Sylva Sylvarum, as mirroring earlier occultist and Neoplatonic attempts to locate hidden wisdom within pre-Christian myths and extract medical wisdom from earlier magical and alchemical treatises. As indicated by the title of his study, however, Rossi claims Bacon ultimately rejected the philosophical foundations of occultism, as well as Aristotelianism, as he came to develop a more modern form of science.

In his study, The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity & the Birth of the Human Sciences, Jason Josephson-Storm also rejects conspiracy theories surrounding Bacon and argues that Bacon’s alleged rejection of magic actually constituted an attempt to purify it of Catholic superstition and to establish magic as a secular field of study and application paralleling Bacon’s vision of science. Furthermore, Josephson-Storm argues that Bacon drew on magical ideas when developing his experimental method. Like Paracelsus (1493-1541) before him, Josephson-Storm suggests that Bacon considered nature a living entity, populated by spirits, and argues Bacon’s views on the human domination and application of nature actually depend on a form of animism that spiritualises and personifies nature.