Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. Leonardo da Vinci, the quintessential polymath, transcended conventional boundaries, leaving an indelible mark on art, science, engineering, and anatomy. We remember him best for his ability to observe and capture nature, scientific phenomena, and human emotions in a range of media, from paint to drawings. For many critics, his collected artworks comprise a contribution to later generations of artists matched only by that of his younger contemporary, Michelangelo.

Leonardo’s insatiable curiosity fuelled his mastery across diverse disciplines. His brilliance manifested in key works that continue to captivate the world. Some of these include:

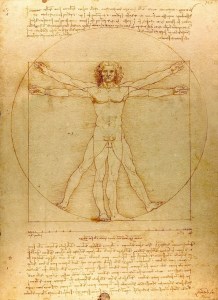

- Vitruvian Man (c. 1490): Whilst working in Milan, Leonardo produced the iconic Vitruvian Man. This intricate illustration, where a man harmoniously fits within a square and circle, revealed his profound exploration of human proportions. It also echoes some ideas common to both sacred geometry and hermetic philosophy, which can be seen echoed in the works of well-known German alchemist, Michael Maier. This is because it contains the proportions of Pi, its sine and cosine, built in, to solve for triangles through trigonometry if two arms and an angle is known, or two angles and one arm, in planes or spheres. This could be interpreted as a connection to hermetic ideas, which often involve the exploration of hidden knowledge and the relationships between different elements of the universe

- The Last Supper (1495–1498): During his Milanese period, Leonardo crafted “The Last Supper,” a masterpiece capturing the pivotal moment of Christ’s betrayal. Painted between 1495 and 1498, this work transcended artistic norms in terms of the unusual (and sometimes irreverent) way it depicts Jesus and his disciples, especially with regards to the use of hand gestures and facial expressions, sparking a host of interpretations and speculations that continue to endure around the significance of the painting.

- Gordian Knot Puzzles (Various Periods): Leonardo’s fascination with complexity manifested in intricate knot puzzles. Although not dated specifically, these puzzles showcased his mathematical prowess, providing glimpses into the workings of his multifaceted mind, even showing up in his paintings as mere decorations, showing us a link between his works. The similarities between the outline of a shield or, indeed, our Greenman ornament, seem fairly uncanny, although it could be perfectly random and just a coincidence. According to a book published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Often incorrectly referred to as lace or embroidery patterns, the Knots are made up of continuously intertwined cords in patterns too intricate for intarsia, soldered wire, or couched thread, unless very much enlarged. They may have been an intellectual exercise for Leonardo, who included mysterious interlaces in the branches of the trees he painted on the ceiling of the Sala delle Asse in the Castello Sforzesco at Milan sometime between I496 and I499·

Janet Byrne, Renaissance Ornament Prints and Drawings

Possibly while he was on his second trip to Venice, in 1505-7, the German artist and printmaker, Albrecht Dürer, created a series of six ornate woodcuts based on Leonardo’s inter-lace drawings known as “The Six Knots” around 1506. These designs were based on a set of engravings by the school of Leonardo da Vinci. Each of these was inscribed Academia Leonardi Vinci, with slight variations. Noone is quite sure who made these and added the inscriptions – Leonardo himself was not known to be a printmaker. Some people wonder if this was a nod to the Platonic Academy of Florence, which was very instrumental in returning many lost Greek manuscripts, preserved by the Arabs, including the works of Plato and other important Neoplatonists such as Plotinus, back to Europe after being lost during the rise of Christianity.

Unconventional Spiritual Beliefs

Speculation looms over Leonardo’s potential involvement with mystery colleges. While lacking historical evidence, conjectures arise from his travels and interactions with scholars, suggesting a hidden connection to esoteric circles.

Leonardo navigated an era dominated by the Catholic Church but also one in which alternative humanistic and hermetic beliefs were beginning to surface, thanks to the reintroduction of important Neoplatonic and hermetic works back into the West. Speculation abounds regarding encoded knowledge in his works, strategically designed to avoid ecclesiastical scrutiny. This speculation permeates his career, reflecting his desire to explore ideas that challenged prevailing religious doctrines.

In the Templar Revelation, for example, authors Lyn Pinknett & Clive Prince claim that Leonardo may have believed that John the Baptist was actually a more important religious figure than Jesus, and that Jesus may actually have had a romantic relationship with, or been married to, Mary Magdalene, which is in line with what scholars appear to have found in the gnostic gospels (Gospel of Phillip) in Nag Hammadi Library. This has been fully explored by scholars such as Margaret Starbird in her book, The Woman with the Alabaster Jar.

Further, Lyn Pinknett & Clive Prince speculate that in The Last Supper, the person in the painting seated, from a viewer’s point of view, to the left of Jesus is Mary Magdalene rather than John the Apostle, further confirming that Leonardo may have believed this heretical notion. They also point out that their body angles form the letter M, a reference to the Magdalene, and that she and Jesus are dressed in similar but oppositely coloured clothes, a negative image of each other. They also mention a number of other signs: a mystery knife pointed at one of the characters, that Leonardo da Vinci himself is in the painting with his face pointing away from Jesus, and that Jesus is confronted by an admonishing hand to his right making “the John gesture,” an index finger pointing up (see right). You can find out more their work, and how it is connected to Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, via this documentary on YouTube.

Leonardo & Hermeticism

During the Renaissance, there was a heightened interest in Hermetic thought, which became a topic of discussion in scientific, philosophical, and artistic circles. Scholars of the time believed that Hermeticism held profound wisdom that had been lost to Europe during the early art of the Christian Era, that could lead to the revitalization of intellectual and spiritual life in Europe.

Hermeticism refers to the spiritual, philosophical, and magical tradition associated with the writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a legendary Hellenistic figure who was conflated with the ancient Greek God Hermes and the Egyptian god of wisdom and scribes, Thoth. These writings, known as the Hermetica, deal with subjects such as cosmology, spiritual illumination, and theurgy. The Hermetic tradition was revived in the Renaissance and had a significant influence on the intellectual and cultural milieu of the time.

However, some sources suggest that Leonardo had little interest in religious matters and, beyond an interest in sacred geometry partly driven by his artistic concerns and partly by his friendship with Luca Pacioli, had no connection with the Hermetic and Cabalistic occult traditions widespread among Renaissance intellectuals.

Was Leonardo Gay?

Some have speculated that Leonardo may have become disillusioned with traditional religion because he was a homosexual (he was accused of sodomy in 1476). and, his unconventional lifestyle (and ‘unclean desires’ according to the church) may have influenced his views on conventional religion, which held that marriage could only take place between a man and a woman.

He certainly seems to have had mixed feelings, for example, about his protege, Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, who is described as one of Leonardo’s students and a lifelong companion and servant, who was also the model for Leonardo’s portrait of St. John the Baptist. He joined Leonardo’s household on St Mary Magdelene’s day at the age of ten as an assistant. Giorgio Vasari describes him as “a graceful and beautiful youth with curly hair, in which Leonardo greatly delighted”. However, in his journals, Leonardo also refers to him as “a liar, a thief, stubborn, and a glutton,” and reveals that he stole from Leonardo on at least five occasions, and that he had a tendency to get ‘hangry’ when not fed. Interestingly, Leonardo gave him nickname of Salai, based on Sallidin the historical Muslim leader who retook Jerusalem and drove Christianity out of the surrounding areas. Salai means: “Little Devil” or “The unclean one.”

Some historians, such as Elizabeth Abbott, have suggested that this may be because the sodomy accusations may have shamed Leonardo into remaining celibate for the majority of his life afterwards. Such details may also explain Leonardo’s ambivalence towards both Salai, and Muslim-related wisdom (at that time, the hermetica became associated with Mohammet/Mohammed/Islam because it had been preserved by the Persians after Christians began persecuting paganism in the 4th century CE, and had then been recovered when hermetic tracts were translated from Arabic into Latin by Marsilio Ficino and other members of the Platonic Academy.

In conclusion, while Leonardo da Vinci was a key figure in the Renaissance and certainly moved in circles where Hermetic ideas were discussed, but there’s no definitive evidence to suggest that he was directly involved with Hermeticism.