Sir Henry Neville (1562-1615) was an English courtier, politician and diplomat, and a prominent figure in Elizabethan and Jacobean England.

His life unfolded against the backdrop of a dynamic period in English history, marked by political intrigue, cultural flourishing, and the emergence of literary giants. He was noted for his role as ambassador to France as well as his unsuccessful attempts to negotiate between James I of England and the Houses of Parliament. According to one source, “His advice was at all events not to James’s taste. In the first session of 1610, he advised the King to give way to the demands of the House of Commons.”

Neville received his early education at Merton College, Oxford, a prestigious institution that played a pivotal role in shaping the minds of many scholars during the Renaissance.

Henry Neville hailed from a distinguished family with strong connections to the court. He was born in Billingbear, Berkshire, and was the first son of Sir Henry Neville I, a Member of Parliament and a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber to King Henry VIII.

Neville distinguished himself by acquiring many titles himself. He was made Groom of the Privy Chamber in 1546, Gentleman of the privy chamber in 1550, was knighted on 11 October 1551 and appointed High Sheriff of Berkshire for 1572. He was elected to Parliament as Knight of the shire for Berkshire five times, from 1553 to 1584.

Neville’s political career began to flourish in his early years. He entered Parliament in 1584, representing Berkshire. His political acumen and eloquence quickly gained attention, paving the way for a trajectory that would see him become a significant player in the political landscape.

Neville’s diplomatic service further underscored his importance in the Elizabethan and Jacobean courts. He held various diplomatic posts, including an ambassadorship to France in 1599. These roles allowed him to navigate the intricate web of European politics, contributing to the diplomatic finesse of the English court. aside from this appointment, Neville was fairly well-travelled, having done the Grand Tour in 1578 after matriculating from university during which he met the astronomers Johannes Praetorius and Tycho Brahé, as well as the humanist, Andreas Dudith.

Despite his earlier successes, Neville’s political career took a challenging turn. In 1601, he became entangled in the Essex Rebellion, a failed coup against Queen Elizabeth I. Neville was implicated and spent years imprisoned in the Tower of London. His release came only after the ascension of James I to the throne in 1603.

After his release, Neville largely withdrew from active political life. He spent his remaining years in contemplation and wrote a notable work, Parliamentum Pacificum, in which he advocated for a parliamentary-run government. In many ways, his socio-political views echo those of Sir William Cecil, in whose household he was privately educated before he went to university. It may also be notable that while working as an ambassador in Paris, he was called a ‘great puritan’ by a Catholic detractor. Interestingly, after marrying Anne Killigrew, he settled in the fervently Protestant parish of Mayfield, in East Sussex, on an estate which he inherited from his mother, Elizabeth Gresham.

Sir Henry Neville passed away on 10 July 1615, leaving behind a legacy that spans politics, diplomacy, and literature. His life, marked by political highs and lows, remains a subject of fascination, particularly for those intrigued by the mysteries of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras.

Neville’s legacy is multifaceted. His contributions to politics and diplomacy, coupled with his connections to key literary figures of his time, have elevated his historical significance. The enigmatic aspects surrounding his name in the context of Shakespearean authorship debates continue to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike, adding layers to the complex narrative of this intriguing historical figure.

THE SHAKESPEARE CONNECTION

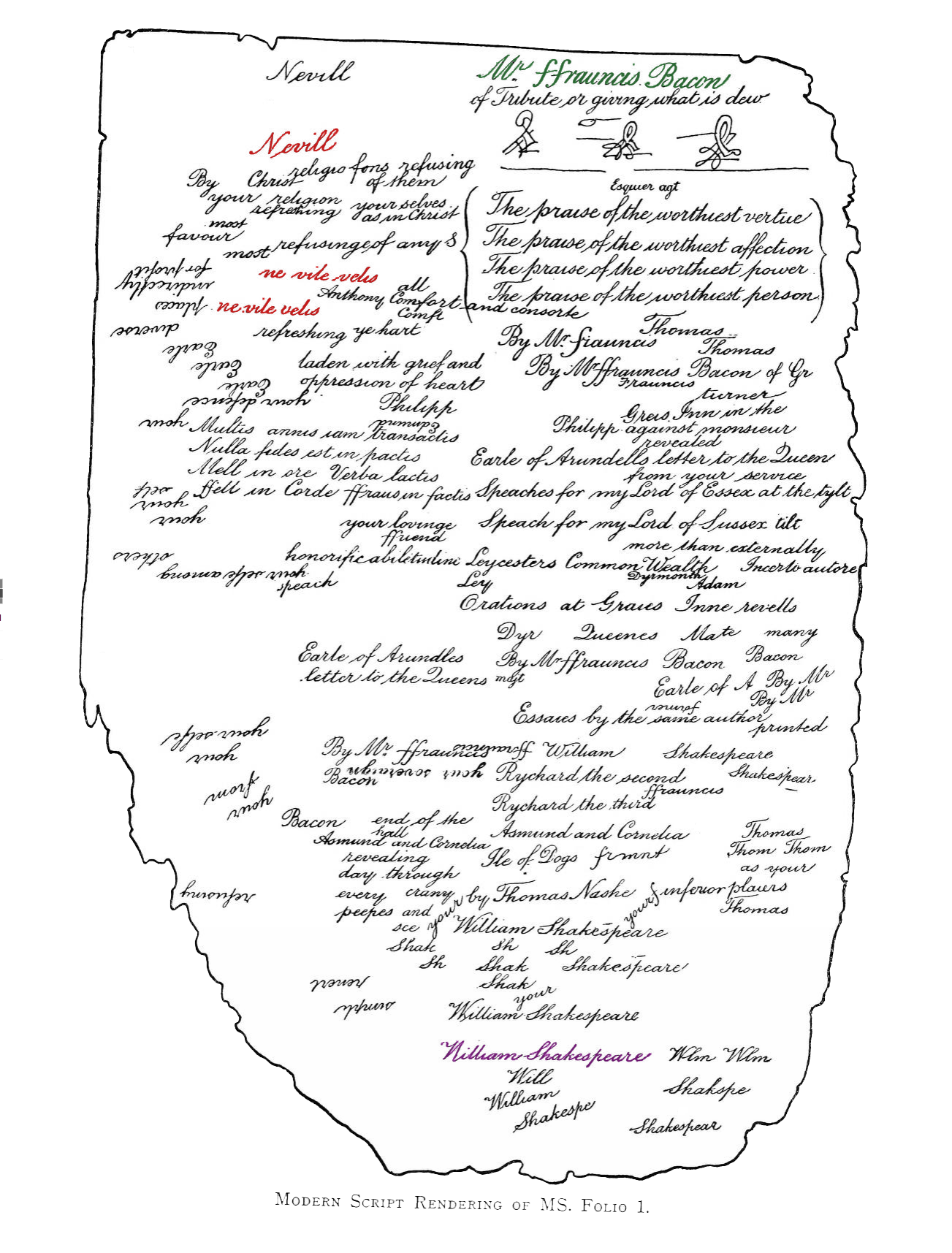

Henry Neville’s life becomes particularly intriguing when his name is intertwined with the literary tapestry of the time. His connections with the likes of William Shakespeare and Francis Bacon have sparked considerable speculation and interest among scholars. The Northumberland Manuscript (below), which features Neville’s name alongside that of Shakespeare and Bacon, has fuelled debates about authorship and collaboration. The Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship has also published an extensive paper on the subject.

In 2005, Neville was put forward as a candidate for the authorship of Shakespeare’s works by authors Brenda James and William Rubenstein. This may be because his life parallels the accepted course and chronology of Shakespeare’s works. Also, many of the books in Neville’s library are annotated with notes relevant to Shakespeare plays. In addition, a conspiracy based on codes and ciphers hidden within his plays and the dedication of Shakespeare’s sonnets, posits that Ben Jonson attributed the First Folio to William Shakespeare in order to hide Neville’s authorship.

Much of the evidence for these theories centres around two documents known as the Tower Notebook and the Northumberland Manuscript. Henry Neville’s name is boldly etched into the manuscript alongside his distinctive motto. This triad of names, each a formidable force in the intellectual landscape of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, invites us to consider the intricate interplay of minds that crafted and contemplated these pages.

In addition, there is also the so-called Tower Notebook, a 200 page manuscript from 1602 that outlines a series of royal protocols, which some alternative historians have asserted to be the work of Neville, despite it not bearing Neville’s name or containing any text in his handwriting. Much emphasis is paced on one page of the notebook containing descriptions of protocols for the coronation of Anne Boleyn which theorists allege are similar to the stage directions given in Henry VIII, a play Shakespeare co-wrote with John Fletcher. The scholarly consensus is that the scene in question was written by Fletcher.

The presence of William Shakespeare, the celebrated playwright and poet, and Francis Bacon, the polymathic philosopher and statesman, side by side raises profound questions about authorship, collaboration, or perhaps shared intellectual circles. It is worth noting that Neville was related to Bacon by birth – his father’s third wife, Elizabeth Bacon, was Francis Bacon’s half-sister.

As we peer into the intricacies of this manuscript, we are not merely examining words on a page; we are decoding a cryptic dialogue between literary giants and political minds. The Northumberland Manuscript transcends its physical form, inviting us to step into the shoes of those who orchestrated this literary symphony. It beckons us to question, to speculate, and to appreciate the magnitude of a moment where the names of Shakespeare, Bacon, and Neville coalesce, leaving an indelible mark on the pages of history and the annals of literary intrigue.

However, it’s important to note that the claim of Neville being the real author of Shakespeare’s works is a topic of ongoing debate among scholars. The mainstream academic consensus still attributes the works to William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon.

The Merry Devil of Edmonton was entered into the Stationers’ Register in 1607, with authorship initially attributed to Sir George Buck, Knight. However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that attributions in the Stationers’ Register didn’t always guarantee actual authorship. Some believe the actual author was William Shakespeare.

Others have speculated that it was the work of Sir Henry Neville, because the play appears to display a knowledge of local towns around Billingbear, Neville’s family seat, including a Windsor inn, as well as a local tale called Herne the Hunter.

However, there is a caveat: In that era, works were frequently registered under the name of a renowned figure to enhance sales. Despite its Stationers’ entry and the absence of an author’s name on the title page, the true origin of this captivating play remains uncertain, introducing an extra layer of mystery to its historical narrative.

The Merry Devil takes its place as one of the publications that carry the signature of block C with its key attributes (including some possible damage) attributed to the printer Valentine Simms. The printing error (ink bubble) is a possible sign that the group had been printed together at the same time.

The problem and the reason why this publication was highlighted is simple – it’s not printed by Simms. While the rest of the group is printed under the name Simms, this publication sharing the same attributes is printed by Henry Ballard. (see the frontispiece)

This is problematic as being printed at the same time its clearly a sign of something strange occurring. A quick examination of the front page unveils something very interesting.