Elias Ashmole (1617–1692) was an English antiquary, politician, officer of arms, astrologer, freemason and student of alchemy. He supported the royalist side during the English Civil War, and at the restoration of Charles II, and as a result, he was rewarded with several lucrative offices. He as also a founding member of the Royal Society.

Ashmole was born on 23 May 1617 in Breadmarket Street, Lichfield, Staffordshire. His family had been prominent, but its fortunes had declined by the time of Ashmole’s birth. His mother, Anne, was the daughter of a wealthy Coventry draper, Anthony Bowyer, and a relative of James Paget, a Baron of the Exchequer. His father, Simon Ashmole (1589–1634), was a saddler, who had served as a soldier in Ireland and Europe. Elias Ashmole attended Lichfield Grammar School (now King Edward VI School) and became a chorister at Lichfield Cathedral.

BIBLIOPHILE & ANTIQUARIAN

Like John Dee and Francis Bacon, Ashmole was an antiquary and book collector, with a strong Baconian and Paracelsian leaning towards the study of nature. His library reflected his intellectual outlook, including works on English history, law, numismatics, chorography, alchemy, astrology, astronomy, and botany. Although he was one of the founding Fellows of the Royal Society, a key institution in the development of experimental science, his interests were more aligned with the mystical rather than the scientific.

Perhaps as a result of his time as an officer in the army during the English Civil War, Ashmole learned (and became interested in) coding and ciphers between 1643-5, and began using them in his journals to hide his private thoughts from prying eyes from 1645 onwards. He also used them to translate esoteric treatises and texts, including John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica which he ‘translated’ into a cipher version using a code invented by John Willis, author of The Art of Stenographie (1617). He was also interested in the work of the famous cryptographer and stenographer, the Abbot Trithemius.

Throughout his life, he was an avid collector of curiosities and other artefacts, many of them acquired from the traveller, botanist, and collector John Tradescant the Younger. as part of his legacy, Ashmole donated most of his collection, his antiquarian library and priceless manuscripts to the University of Oxford to create the Ashmolean Museum.

Alchemy, Magic & Astrology

The Dee’s

During the 1650s, Ashmole devoted a great deal of energy to the study of alchemy, publishing the Fasciculus Chemicus under the anagrammatic pseudonym of James Hasolle. Perhaps a nod to the trend towards ciphers and wordplay that was common at the time. Perhaps ironically, it later transpired that the work was actually an English translation of two Latin alchemical works, one by Arthur Dee, the son of John Dee. Ashmole had thought him dead. Upon discovering that he was, in fact, just working abroad as a physician to the Emperor of Russia, Ashmole was forced to seek his retrospective permission to publish what was essentially Dee’s work.

Ashmole was also lucky enough to come by some lost papers from John Dee‘s ‘spiritual diaries’ in 1672 which had been hidden in a trunk and later found and given to him by a mutual acquaintance. These covered the period between December 1581 and May 1583, thus preceding those extracts published by Meric Casaubon in 1659. They later became known as the Liber Mysteriorum Books I-V. Ashmole meticulously transcribed all five books, eventually publishing them, along with a note detailing how he had acquired them, in Mercurius Britannicus, a periodical that ran from 1643 to 1645, and was edited by Elias Ashmole himself. It is fair to say that Ashmole remained fascinated by Dee all his life and, as the ultimate magus figure, ‘a man with whom he clearly identified.’

Theatricum Alchemicum

In 1652, he published his most important alchemical work, Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum, an extensively annotated compilation of metaphysical poems in English. The book preserved and made available many works that had previously existed only in privately-held manuscripts.

Despite being very knowledgeable on the subject, there is little evidence that Ashmole conducted his own alchemical experiments, suggesting that he was not a ‘puffer,’ but rather a spiritual alchemist.

He may also have been part of some form of hermetic initiatic circle, referring to himself as the spiritual son of William Backhouse, who ‘adopted’ him in 1651, becoming, like Hermes Trismegistus, his mentor and teacher. In this sense, he was imitating a long-held tradition found within the Corpus Hermeticum of acquiring wisdom via the pupil-teacher dialectical relationship that had been popular during classical times. According to Ashmole, Backhouse “intytle[d] me to some small parte Of grand sire Hermes wealth [sic]”.

Notoriously private, not much is known about Backhouse except that he was a “respected figure in a network of people involved in occult and philosophical studies” according to Jennifer Speake; a “most renown’d chymist, Rosicrucian, and a great encourager of those that studied chymistry and astrology” according to Anthony Wood; and a “quiet, secretive man of an inventive mind […] combining a gift for languages with a graceful poetic vein” according to C. H. Josten.

Astrology

Ashmole was also very interested in astrology, and was friendly with some of the celebrity astrologers of the day, including George Wharton and William Lilly.

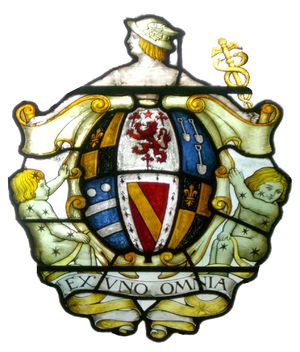

His interest in astrology and alchemy is evident in his coat of arms which contains the motto ‘EX UNO OMNIA’ (from one comes all), echoing the hermetic idea of the one in the many, as expressed in the Emerald Tablet. On either side of his shield are the twins of Gemini, his Sun sign. At the top of the shield , we find the personification of the planet Mercury, ruler of alchemy, holding his healing caduceus or magic ‘rod.’

FREEMASON & ROSICRUCIAN LEANINGS

According to Tobias Churton, Ashmole almost certainly believed that the Fraternity of the Rose Cross actually existed in some form or other. In a note found amongst his personal papers, now held at the Bodleian Library. , he outlines in cipher: “The Fratres RC : live about Strasburg : 7 miles from thence in a mon[a]st[e]ry.” (Ashmole Mss., 1459; ff. 280–82; ff. 284–31)

Despite a stern defence from his friend, John Gadbury against Anthony Wood, who accused Ashmole of being a Rosicrucian, it would appear that Ashmole was an ardent supporter of Rosicrucianism. So much so, that he privately expressed an interest in joining the fraternity. Proof of this can be found appended to a handwritten copy of the Fama Fraternitatis. Here we find what appears to be a fervent petition to “the most illuminated Brothers of the Rose Cross” that he, Elias Ashmole, might be admitted to their fraternity. (Ashmole Mss., 1478; ff. 125–29)

He was an early freemason, writing in his diary on16 Oct 1646 that: “I was made a Free Mason at Warrington in Lancashire, with Coll: Henry Mainwaring of Karincham [Kermincham] in Cheshire.” We do not know much else about his freemasonry activities, but suffice it to say, he may well have chosen to join the fraternity, not just as a way of networking, but also as a substitute for his desire to be part of the Rosicrucian fraternity.

A scholar and man of many interests and occupations, Ashmole was, like Leonardo Da Vinci before him, the last of the Renaissance men. According to Tobias Churton, he lived ‘in an era that was slipping away from the limitless ambition of the Renaissance philosophy of human dignity,’ and was, instead ‘beginning to focus sharply on the earthly virtues of patient experiment and worldly profit.’