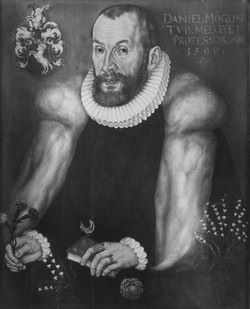

Daniel Mögling (1596-1635), born in Böblingen and passing away in 1635 in Butzbach, stands as a luminary figure in the realm of German alchemy, leaving an indelible mark on the esoteric landscape of the early 17th century. His life and contributions extend beyond the mere transmutation of metals, delving into the symbolic and spiritual dimensions of alchemy.

Mögling served as the personal physician and court astronomer to Philip III, Landgrave of Hesse-Butzbach from 1621-1635. His role involved both medical practice and astronomical observations. In this respect, he shares

Also known by pseudonyms such as Valerius Saledinus, Theophilus Schweighardt, and Florentinus de Valentia, Mögling was a notable figure in the early history of the Rosicrucian movement and in hermetic circles. Furthermore, Mögling’s association with alchemy adds layers of mysticism to his legacy.

Alchemy & ROSICRUCIANISM

During Mögling’s era, alchemy underwent a transformative evolution. No longer confined to the pursuit of material wealth through the transmutation of base metals into gold, alchemy became a metaphorical and spiritual journey.

Certainly, during this period, alchemy became a common metaphor for spiritual initiation, often depicted as an ascent up through seven levels, whether a flight of stairs, ladder or tower, as we find in Johannes Valentin Andreae‘s Chymical Wedding.

Mögling, residing in a time when the Rosicrucian movement was gaining momentum, found himself at the crossroads of alchemical, mystical, and philosophical ideas, all of which found their way into Rosicurcianism. In this respect, he shares a lot in common with other key figures in our story, such as Elias Ashmole.

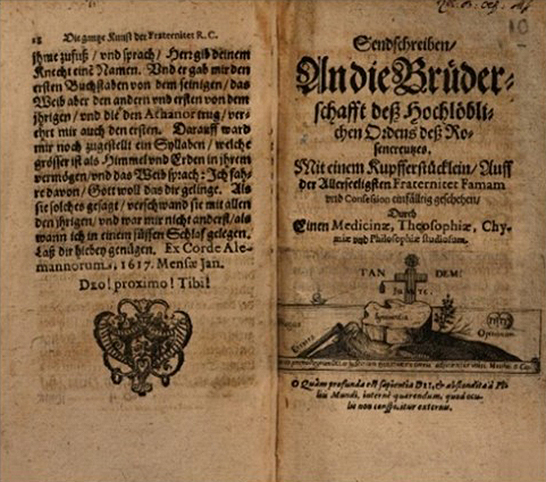

Indeed, Daniel Mögling’s association with rose cross-themed publications, particularly under pseudonyms, adds an intriguing dimension to his literary and esoteric pursuits. Let’s delve into the significance of the mentioned works:

Key Publications

Speculum Sophicum Rhodostauroticum (Mirror of the Wisdom of the Rosy Cross, 1618)

The title itself suggests a connection to the Rosy Cross, emblematic of spiritual and alchemical pursuits. Mögling, under this pseudonym, likely explored mystical and esoteric concepts, contributing to the broader discourse of Rosicrucianism.

Mögling’s use of the pseudonym Teophilus Schweighardt Constantiens for this work, which aligns with Rosicrucian themes prevalent during the early 17th century. It is also in keeping with the pseudepigraphic tradition we find in Hermeticism where writers of esoteric texts would frequently attribute authorship of their work to the mythical teacher and sage, ‘Thrice Great Hermes’ as a means of simultaneously adding an air of authority to their work, and enabling them to remain anonymous.

It is also in this Mögling work that we are introduced to the concept of Ergon and parergon (Work and by-product); oratory and laboratory – themes we will return to again nd again on our journey.

Jhesus Nobis Omnia – Rosa Florescens (1617):

Published under the pseudonym Florentinus de Valentia, this work’s title, translating to “Jesus Gives Us Everything – The Blooming Rose,” further underscores Mögling’s engagement with Christian and Rosicrucian symbolism. The use of the rose as a metaphor for spiritual flourishing is a common motif within Rosicrucian literature.

Pandora Sextae Aetatis (1617):

“Pandora Sextae Aetatis” translates to “Pandora of the Sixth Age.” The mention of the sixth age may carry symbolic significance, possibly referring to a period of transition or enlightenment. This work, situated within the broader context of Mögling’s rose cross-themed publications, explores esoteric and alchemical themes associated with the Rosicrucian movement.

stArting point for the green man journey

This gentleman marks the inception of the Green Man journey and begins our path of initiation deeper into the Rosicrucian mysteries.

The discovery of a seemingly simple yet peculiar hand gesture was a modest find that ignited an enduring fascination way back in 2014, propelling me into a realm of unceasing intrigue and a ten year odyssey into the Rosicrucian mystery and the secret world of books.

It is also in Mögling’s publications, especially his alchemical and Rosicrucian books, that we first discovered our Green Man ‘ground zero,’ so to speak – Block A of the Green Man carvings.

These led to what would become some of the key signatures and signposts along the trail of the Green Man.

Let’s look at each in turn.

Secret Hand Gestures

Interestingly, we also see a similar hand-on-heart gesture being employed in a portrait of Robert Fludd (above right). Woven into his garment also appears to be the face of a green man, perhaps signalling his sympathies with some kind of secretive movement or organisation, similar to a Masonic handshake?

Interestingly, we also see hand gestures being employed to dramatic effect in the work of Leonardo da Vinci – a technique he may have borrowed from the language and conventions found within Christian medieval illuminated manuscripts, especially in relation to depictions of the saints.

For example, within Greek Orthodox and early Christian iconography, the gesture of blessing, known as the ‘benediction hand,’ actually forms the letters IC XC, an abbreviation for ‘Jesus (IHCOYC) Christ (XPICTOC)’ in Greek, and includes the first and last letter of each word. Thus, the hand that blesses always reproduces, via gestures, the name of Jesus – the “Name that is above every other name.”

Certainly, within the alchemical literary tradition, of which Mögling was a part, it was commonplace to use hand gestures to conveyed secret knowledge whilst also veiling these esoteric truths from the uninitiated.

The Green Man Motif

One of the enigmatic aspects of Mögling’s legacy lies in his integration of the Green Man within his publications.

The Green Man, as the linchpin of this intricate tapestry, becomes the key to unravelling the concealed truths within Mögling’s works. It symbolizes not only the interconnectedness of nature and the divine but also the transformative journey of the alchemist seeking spiritual enlightenment.

This verdant figure, with its intertwining human and vegetative elements, emerges as a central cipher in unlocking the concealed meanings scattered throughout Mögling’s other carvings.

The Green Man, a motif found in various cultures, symbolises the spirit of the wild and the rejuvenating power of nature. The carving’s resemblance to Pan, particularly in the depiction of horns, raises the possibility that Pan could indeed be the inspiration behind the Green Man imagery, with its links to foliate printer’s ornaments.

The motif of horns as antennae, connecting individuals to higher powers, extends beyond Pan to figures like Moses in history. The horns on Moses, often depicted in artistic representations (see above), may symbolise his direct communication with God, reinforcing the idea that individuals bearing such symbols are conduits between the earthly and divine realms.

In essence, the intertwining of Pan, the Greenman, and figures like Moses through the shared symbolism of horns underscores the pervasive motif of divine communication in human history. Whether through mythological deities or biblical figures, the presence of horns serves as a visual language, signalling a connection to higher powers and reinforcing the timeless narrative of mortal communion with the divine.

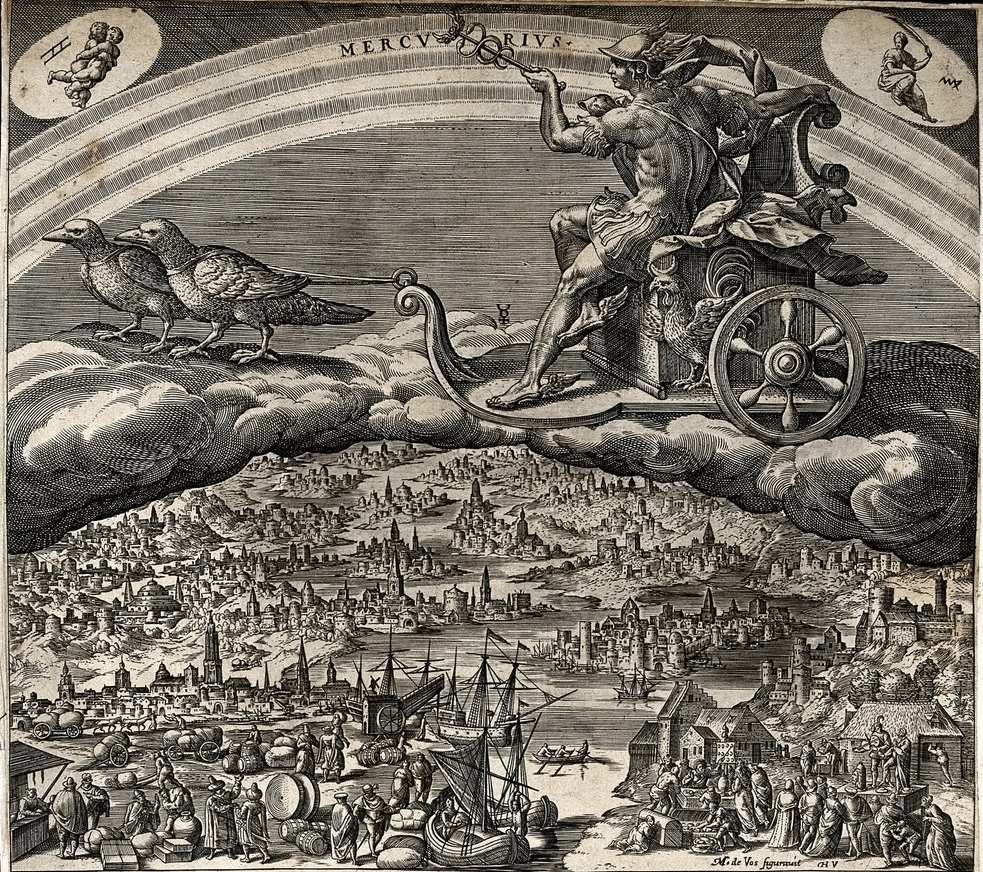

It may also point to the signature winged cap (see below) or lunar ‘horns’ we find atop the sigil for Mercury, who as a composite of the Greek Hermes and Egyptian Thoth, was considered to be the ruler of alchemy.

Like Pan or Puck in Shakespeare’s plays, Hermes is also considered to be a mischievous trickster and youthful nature spirit. His older, wiser counterpart is Saturn, the bearded sage, also known as the ‘elder Mercury,’ the wise older teacher, guide or father figure, who was also associated with Pan because of his lasciviousness. (Satyrs were thought to be quite sexual creatures because half man, half beast.)

It may also be important that important to mention that Moses was thought to be the founder of Kabbalah, something he was alleged to have learned from Egyptian priests whilst living in the court of the pharaohs prior to the Exodus. Legend has it that he later used this wisdom to create the esoteric bedrock of the Jewish faith as a hidden counterpart to the more exoteric 10 commandments. Mogling’s work is filled with references to Kabbalah, especially the cabbalistic Tree of Life – something that is also common to Rosicrucianism. So his use of the Green Man motif in his books seems significant and more than coincidence.

The concept of the Greenman wood block carving as a messenger aligns with the symbolism of the Greenman representing the vital force of nature communicating with humanity. The Green Man, as both symbol and guide, encapsulates the essence of Mögling’s quest and invites those who follow in his footsteps to decipher the mysteries that lie beneath the surface of his intricate carvings.

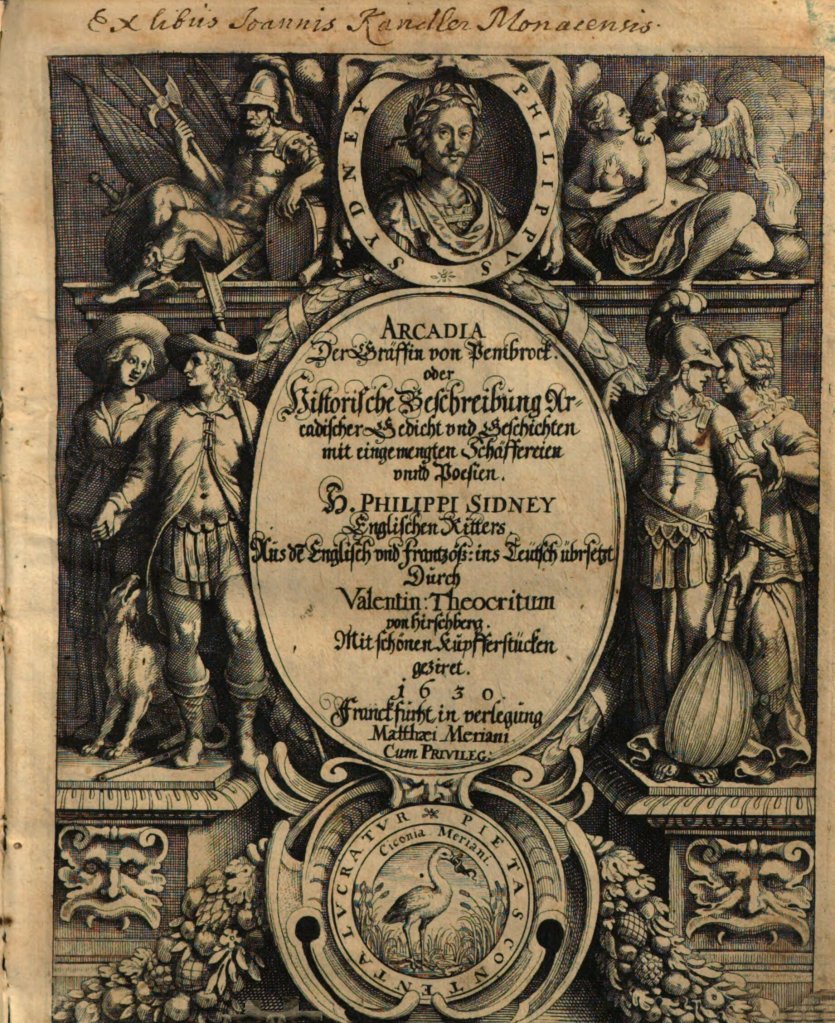

Phillip Sidney’s Arcadia

Daniel Mögling’s decision to translate Philip Sidney’s Arcadia into German adds an interesting layer to his literary endeavours. Arcadia, a pastoral romance, traditionally explores idealised landscapes and themes of love and adventure.

As we delve further into Mögling’s intricate legacy, Arcadia will take on a significant role in our exploration. The translation of Arcadia becomes a bridge, connecting seemingly disparate people like and elements of Mögling’s intellectual pursuits and hinting at the deeper layers of meaning that will unfold during our narrative.

While seemingly divergent from Mögling’s rose cross-themed publications, this translation may hold clues to deeper connections. For one thing, it echoes the Utopian aspirations we have already seen as being so prevalent within Protestanism (and espoused by figures such as Francis Bacon, Sir William Cecil and Johannes Andreae) and in colonial endeavours focused on the New World, which are exemplified in men like William Alexander.

For another, it employed the use of “speaking pictures” within the text, which resonates with Mogling’s use of hand gestures within his publications. These are not the same as visual illustrations but serve as powerful metaphors – a way to turn “barren philosophy precepts into pregnant images of life,” as Fulke Greville puts it in his dedication to Sidney’s work. William Lilly referred to his use of such images as ‘hieroglyphics.’ This, along with the use of codes and ciphers within letters and written publications, seems to have been a fairly common practice during the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, perhaps as a way to preserve hidden knowledge but also to protect people from persecution.

William Scott notes Sidney’s debt to Theophrastus’s Charaktēres and highlights the “describing notes or characters” of his persons in a similar way to Myers Briggs Types or astrology sun signs today. Theophratus was a student of the philosopher, Aristotle. He links us not just to the Platonic and Neoplatonic traditions so prevalent within Western Esotericism, but also to the notion of science as ‘natural philosophy’ – something echoed in the work of people like Francis Bacon.

Mögling’s choice to focus on the notion of Arcadia, which is all about nature in its paradisal or original state, may also connect more directly to our Green Man theme via the figure of Pan as a nature god—a reflection of pastoral harmony and the fusion of the natural and divine.