Although much has been said and written about the existence of a Rosicrucian Order, along with speculation about the possible membership of many illustrious candidates who might have been affiliated with this secretive organisation, the historical evidence suggests that the order did not formally exist until the ‘Neo-Rosicrucian’ period.

Author and historian, Tobias Churton has successfully argued that the figure of CRC and the Rosicrucian lore detailed in the first two books published under the banner of the Rosicrucian Brotherhood, are largely mythical – the secret invention of two men from the Tubingen circle: Johannes Valentin Andreae and Tobias Hess. For him, ‘the plain evidence is overwhelming,’ – the story is meant to be symbolic/allegorical and not to be taken literally.

The same went for the organisation itself, which, outside of the Tubingen Circle, seems to have been largely mythical – a metaphor for the Brotherhood of Man: a utopian ideal that often went hand in hand with apocalyptic prophecies of a coming Golden Age that would come to be be associated, first with the biblical Book of Revelations, then with the Reformation; and later on, with both the Enlightenment and the New Age movement.

In fact, in the second book, the Confessio Fraternitatis, the authors spell out that membership of this elusive brotherhood, resided in one’s individual ‘ability to read the living signs in nature.’ Notice the book metaphor, and its connection to the notion of divination and revelation – being able to read the signs that are already coded into the Universe. Thus, a symbolic orientation to life and the ability to read “those great letters and characters which the Lord God hath written and imprinted in heaven and earth’s edifice ” is the essential badge of membership to the Rosicrucian Order.

In other words, those alchemists and followers of the western esoteric tradition, particularly the hermetic streams, were ALREADY considered to be fellow members – part of a group of like-minded seekers of the ‘perennial wisdom.’ So in essence, an intellectual and spiritual movement, rather than a conspiracy of illuminati-type power brokers such as a Da Vinci Code-style Priory of Sion.

As Churton puts it:

Election to the invisible brotherhood is thus by consciousness only. True brothers will recognize what is essential of themselves in the other.

Despite all of this, it seems as though the author/s of the FAMA were ambivalent about publishing it, and in fact, did not give permission for its first print in 1614. However, once the work was out there, it seems to have taken on a life of its own- in modern parlance, we might say that it ‘went viral,’ leading to a chain reaction of responses, critiques and sympathy publications from various quarters.

In essence, then, the first wave of so-called Rosymania, took the form of a literary movement, or what some have called the ‘battle of the books.’

letters, codes & ciphers

That being said, there was still a need for secrecy – after all, one of the first people to pen a response to the FAMA, a a Tyrolean schoolmaster, alchemist and Paracelsus enthusiast named Adam Haslmayr whose 1612 response to a handwritten version of the FAMA was published as part of the first printed edition in 1614, was arrested and sentenced to be a galley slave at Genoa until he fully recanted what he’d said in his ‘Answer to the FAMA’.

Indeed, due to the ever-present threat of persecution during this period, a lot of the esoteric knowledge contained in these books – and conversation they provoked – had to be kept private. Often, this meant using secret codes embedded within the text.

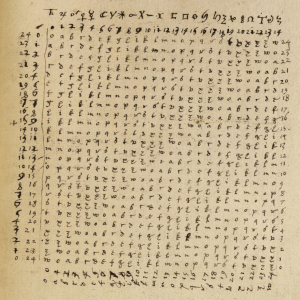

The invention of steganography helped enormously with this endeavour. It may be no coincidence that one of the first books dealing specifically with cryptography and steganography in sacred texts was the notorious German theologian and polymath named Trithemius (1462–1515), whose book the Stenographia was acquired by John Dee the year before (1563) he published his famous Monas Hieroglyphicus (Antwerp, 1564), and whose work is quoted by many aspirant Rosicrucians, including the English astrologer, William Lilly (1602-1681), who published a translation of another of Trithemius’ works as part of a compendium of prophecies in 1666, and admitted to using codes in his work to protect himself from persecution.

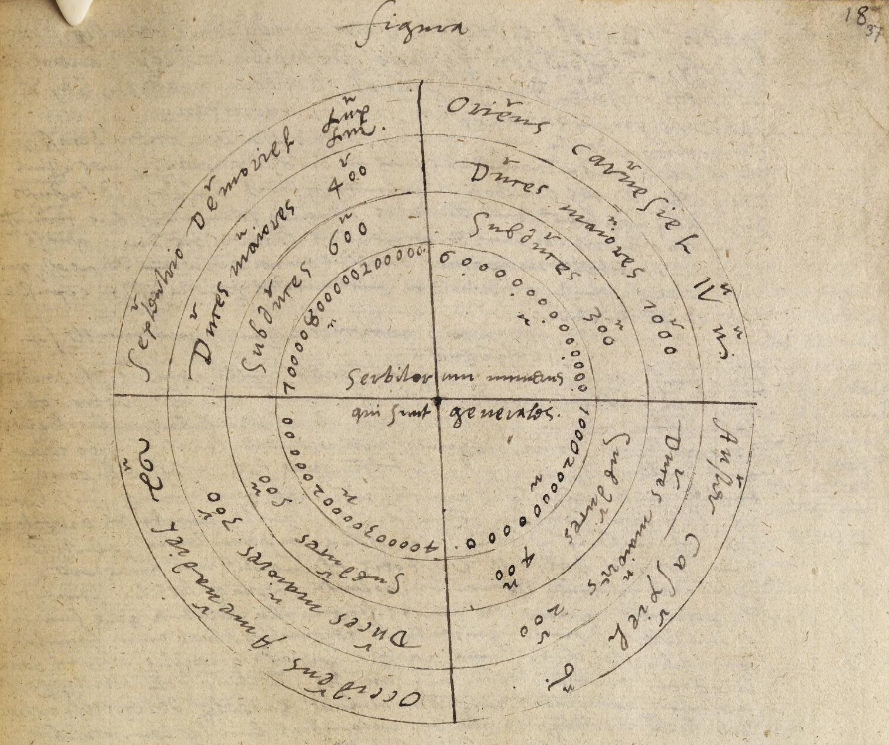

A transcript of some code ciphers and a drawing taken from Johannes Trithemius‘ (1462-1516) Steganographia in the hand of Dr John Dee. Steganography is the act of writing in a secret code.

John Dee, of course, was also known to be involved in intelligence gathering for Queen Elizabeth, and so all this coding served multiple purposes. Whether due to religious paranoia or political plots and counterplots, this was an era in which ‘codes, ciphers, anagrams, acrostics and emblems were familiar concepts.’ Certainly, they were fairly commonplace in Elizabethan and Jacobean England where they were used sometimes for amusement/entertainment, but also, on a more serious level, to prevent state secrets from being discovered, and to protect the monarch from coup plots. This was, after all a ‘high stakes environment involving many political factions and religious uncertainty and where the wrong word could often mean death or imprisonment. Secrecy was an absolute necessity in many situations.’

Aside from the need for secrecy, there was also a philosophical aspect to all this coding: many students of magic and the esoteric, including Dr Dee, who was connected to the publishers of the FAMA via his assistant, Edward Kelley, believed that coded language and symbols held the key to communicating with divine beings such as angels, and perhaps even understanding the secrets of Creation.

This idea fed into the assertion made by Greek Platonists and philosophers such as Pythagoras (whose work was being reintroduced to the West via Renaissance humanists such as Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola) that numbers and geometry underpinned the structure of the entire Universe, whilst Chaldean astrologers talked of the ‘heavenly writing’ of the gods, which their system was designed to decode.

This idea was also what underpinned the esoteric Jewish tradition of Kabbalah, which maintained that canonical religious texts often contained layers of meaning that could only be decoded by using a system known as gematria, which correlated letters with numbers. In fact, this idea became so commonplace at one time, that people would often use the word ‘cabal’ to mean a puzzle, hidden code or secret meaning in general without necessarily referring to cabbalistic practices per se. In fact, Mirandola was the founder of the tradition of Christian Kabbalah, a key tenet of early modern Western esotericism, which was often often transliterated as Cabala (also Cabbala) to distinguish it from the Jewish form (Kabbalah) and, in turn, from Hermetic Qabalah.

In this way, sciences like astronomy and geometry, and arts like writing, actually formed two halves of the same pursuit, which could best be summed up as ‘natural philosophy,’ which held that nature (physics) and spirit were not separate and should be studied in unison. Hence, the development of more holistic methods that had both spiritual and chemical aspects, such as alchemy.

HERMENEUTICS

These ideas also slotted neatly into a long-held medieval tradition concerning the creation (and interpretation) of illuminated manuscripts known as hermeneutics, which rather synchronistically from our perspective, gets it’s name from Hermes, the Greek god of language, speech and meaning, who was also the patron of the hermetic tradition – a pagan god strongly associated with alchemy as well as trickster-like sprites and mischievous elementals such as Ariel in The Tempest, or Puck in a Midsummer Night’s Dream. A figure who, incidentally, is not too dissimilar to our iconic green man…

First introduced by Aristotle, hermeneutics became a methodology for ‘decoding’ the layered meaning of hidden messages embedded within a sacred symbol, image, divine sign or text. So, you could say, it was the complementary opposite of steganography the deciphering of hidden messages, often by the initiated.

This often involved a two-fold process: the intuitive receipt of a ‘code’ or omen, followed by its logical/systematic interpretation using a set method, thus engaging both the left and right sides of the brain. Or what the Italian mathematician, cipherer and astronomer-astrologer, Girolamo Cardano called interpretation ‘by the science and the art,’ again achieving that utopian ideal seen in many Rosicrucian sympathisers, to unite the schism between faith and reason.

Over time, this evolved beyond the walls of the seminary and monastery to include the interpretation of literary texts, leading to what some now call the Four-fold Method of textual interpretation, which divide meaning into four layers:

- Literal – The explicit or ‘plain meaning’ of a text, as expressed by its language, linguistic construction and historical context.

- Moral – The moral lessons or comparative deductions one can derive from that meaning, in the case of, say a parable. How the text might relate to a current situation or personal matter, which can help provide ethical guidance and helpful insight into how to solve difficult dilemmas or problems.

- Allegorical – By unpacking the metaphors or particular archetypes, symbols or meaningful references to previous people or events within a tradition used within a text, one can derive an additional layer of meaning.

- Anagogical – The esoteric or hidden meaning of a text – something often not recognised by the uninitiated. Often known as mystical interpretation, this level of meaning often has a prophetic, initiatic or intuitive component. This is evident in the Jewish Kabbalah, which attempts to reveal the mystical significance of the numerical values of Hebrew words and letters.